The seed that germinated into Jack liberty’s Son was sown while I was standing on Old Bailey Street, with the Central Criminal Court in front of me and the spire of St Sepulchre’s Church across Newgate Street. If I’d been there two hundred years before, there would have been no ‘Old Bailey’ in front of me but the notorious Newgate Prison. On a Monday, the ‘new drop’ gallows would have been hauled across the cobblestones where there is now a tarmac road, and twenty criminals would have been hanged at once.

The seed that germinated into Jack liberty’s Son was sown while I was standing on Old Bailey Street, with the Central Criminal Court in front of me and the spire of St Sepulchre’s Church across Newgate Street. If I’d been there two hundred years before, there would have been no ‘Old Bailey’ in front of me but the notorious Newgate Prison. On a Monday, the ‘new drop’ gallows would have been hauled across the cobblestones where there is now a tarmac road, and twenty criminals would have been hanged at once.

For some of them, their punishment went beyond the end of the rope. When even petty theft was punished with the death sentence, a stiffer punishment was needed for murderers. They were sentenced to be ‘dissected and anatomised’, which denied them a whole body in which to await the Resurrection and supplied trainee surgeons with cadavers on which to learn their trade.

The rookeries of London may have been lawless but there were never enough murderers to supply the needs of the surgical schools. The bodies of lesser criminals found their way to the same slabs, along with anyone else who could be dug up soon

enough after they were buried. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, one of the leading purchaser of cadavers, from the gallows, the grave or wherever else he could get them, was John Hunter, subject of Wendy Moore’s biography The Knife Man.

Grisly as his methods were, we owe a great deal to the man who, more than anyone else, introduced scientific medicine to Britain. His detailed descriptions of human anatomy informed the surgical techniques he tested with considerably more concern for his live patients than many of his contemporaries. His interests extended beyond his own species to make him one of the leading naturalists of his day. He examined many of the specimens brought back by James Cook’s expeditions to Australia and New Zealand, and was one of the early advocates of evolutionary theory. Perhaps his crowning achievement was his mentorship of his first apprentice, Edward Jenner, who left London to pursue a quiet life as a country doctor and naturalist, where he discovered how the cuckoo breeds in other birds’ nests – and then invented vaccination.

Hunter’s collection is preserved by the Royal College of Surgeons, and remains one of London’s hidden gems.

But I didn’t want to fictionalise Hunter. Moore had already written an account as riveting as a novel. I needed something different, and I found what I needed in a different place altogether. I’d first heard of Tom Molineaux, an American slave who became a star of England’s bareknuckle boxing scene, through George MacDonald Fraser’s novel, Black Ajax. In The Celebrated Captain Barclay, Peter Radford told the story of the man who trained Tom Cribb, who twice defeated Molineaux’s challenges to the Championship of All England. It’s a tale of sporting excellence and the absurd decadence of the ‘Fancy’, who spun their passion for gambling on crippling fistfights into an act of patriotism even as they disdained military service against Napoleon’s armies massed across the English Channel.

With a dash of the macabre from Newgate Prison and John Hunter, and something to apply it to in the challenge Molineaux represented to the Fancy’s patriotism. They claimed that boxing demonstrated a staunchness that only an Englishman could show, so it wouldn’t have looked good if a slave-born black American became the Champion of All England. How far would the Fancy go to make sure that didn’t happen? Would they resort to a sort of necromancy that might have made sense to medical science at the time of Cribb and Molineaux’s second bout in 1811?

As I’d entered the realm of Regency race relations, I gave it a little more prominence by giving the protagonist a slave history of his own. At the end of the American War of Independence, many slaves won their freedom by fighting or working for the British. I’d recently read Simon Schama’s Rough Crossings, which describes how many of them changed their names to avoid being returned to their owners under the terms that ended the war. Schama follows the fortune of one man who called himself ‘British Freedom’. If there was a man who called himself ‘Freedom’, there must have been others who called themselves ‘Liberty’.

So into a milieu that had been shaped for him by criminals, pugilists, anatomists, gamblers and errant slaves lumbered Jack Liberty. Can he be blamed if the first thing he does is throw a punch?

~~~~~~

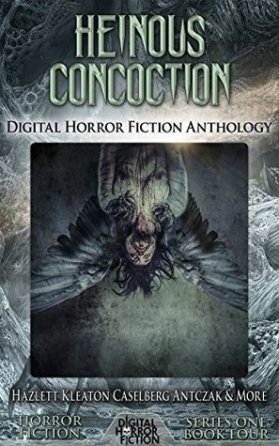

Jack Liberty’s Son was first published in Space and Time #125, Spring 2016, which is available in hardcopy or ebook formats, and republished in the Heinous Concoction Kindle anthology by Digital Fiction.